Making the case

There is a business case for taking climate action. Local governments can use financial tools, such as triple bottom line accounting or asset management, to create informed conversations and build support from elected officials and colleagues, gather data and track performance measures, assess existing and future conditions, uncover hidden costs associated with continuing existing practices, and identifying options using evidence-based methods. These tools include:

- Business cases

- Integrated financial planning

- Lifecycle costing

- Triple bottom line

- Asset management and natural asset management

This section provides a high-level overview of the development of a climate action business case, one that, for example, addresses both climate change mitigation and adaptation. Business cases are essential for setting goals and identifying and evaluating options for taking action to meet those goals.

The business case for climate action also provides a rationale to support government and community initiatives focused on reducing emissions. Business cases for taking climate action identify measures that:

- Focus on reducing GHG emissions

- Include actions that reduce climate impacts while also saving money and result in additional long-term financial benefits

- Integrate mitigation and adaptation approaches such that the return-on-investment is maximized

A business case for climate action supports local governments’ goal of sound fiscal management by demonstrating how to reduce costs, improve service delivery, create jobs, and support local industries, while protecting the environment and human health.[1]

Considerations for developing a business case for climate action include:

Maximizing co-benefits and minimizing conflict between adaptation and mitigation actions

Climate action planning should include both adaptation and mitigation efforts. Low carbon resilience provides a framework for integrating adaptation and mitigation planning and actions.

Understanding existing conditions (baseline evaluation)

Establish a baseline through emissions data and other relevant information. Document the climate impacts already being experienced by your community. Identify what is at risk and the benefits of actions already being taken to reduce emissions and address climate impacts. Tools for identifying a baseline include:

- Emissions indicators to help identify focus areas and targets

- Emissions tools, such as the Climate Action Planner

- Mapping to track flooding, sea level rise, wildfire risk, and other impacts

- Risk and vulnerability assessments

Comparing alternative long-term land use scenarios

Land use decisions, which are linked to transportation demand and behaviour, can influence the extent to which emissions can be reduced. Land use patterns also impact the short and long-term cost of infrastructure and services. Complete communities support socially, economically, and environmentally resilient communities. Tools that help compare land use and development scenarios include:

- Land use modeling can help estimate emissions and other costs and benefits

- Community Lifecycle Infrastructure Costing (CLIC) Tool projects infrastructure costs over 100 years for a range of land use development scenarios. This includes development, maintenance, servicing, and replacement.

Predicting future costs

There are several processes that local governments can use to understand the financial benefits of integrated climate action. These include:

- Lifecycle analysis which estimates the wide range of environmental impacts or costs of a product or project over its entire life. Lifecycle Analysis is closely connected to triple bottom line accounting.

- Lifecycle costing which looks at the costs and benefits of assets (e.g. infrastructure, vehicles, equipment) over their lifetime.

- Asset management is a process used to maximize benefits, reduce risks, and provide sustainable levels of service to communities.

Working across silos with integrated, systems thinking

Actions taken will have socio-cultural, environmental and economic impacts – positive and negative. To evaluate these impacts, consider:

- Triple bottom line accounting which assesses and balances economic, environmental and socio-cultural criteria.

- Complete, compact communities can reduce emissions, infrastructure costs and can increase health benefits.

- Energy reduction and alternative energy use can help communities save money, make money, and become more self-sufficient.

- Reducing and reusing water and wastewater can save money in infrastructure operations and ensure water is available in times of scarcity.

- Natural asset management which involves integrating natural assets into traditional asset management.

- Closed loop approach focuses on keeping resources in use for as long as possible, extracting maximum value from them, and recovering and regenerating products and materials at the end of life (reducing material use and waste).

- Regenerative Infrastructure approach integrates land use planning and infrastructure decisions, working with and enhancing nature’s systems, and utilizing Integrated Resource Recovery (IRR) technologies to recover energy and other resources previously wasted.

Thinking local but acting regional (regional collaboration)

It is often more efficient and effective when communities in proximity work together and learn from each other. This can include:

- Partnerships and collaboration between local governments and Indigenous communities

- Sub-regional and regional planning and collaboration

Identifying additional sources of revenue and funding

These include:

- Integrated financial planning

- Financial tools, incentives and processes

- Other funding sources

Learning from other local governments

Other communities’ successes can be very powerful learning tools. These experiences are captured in:

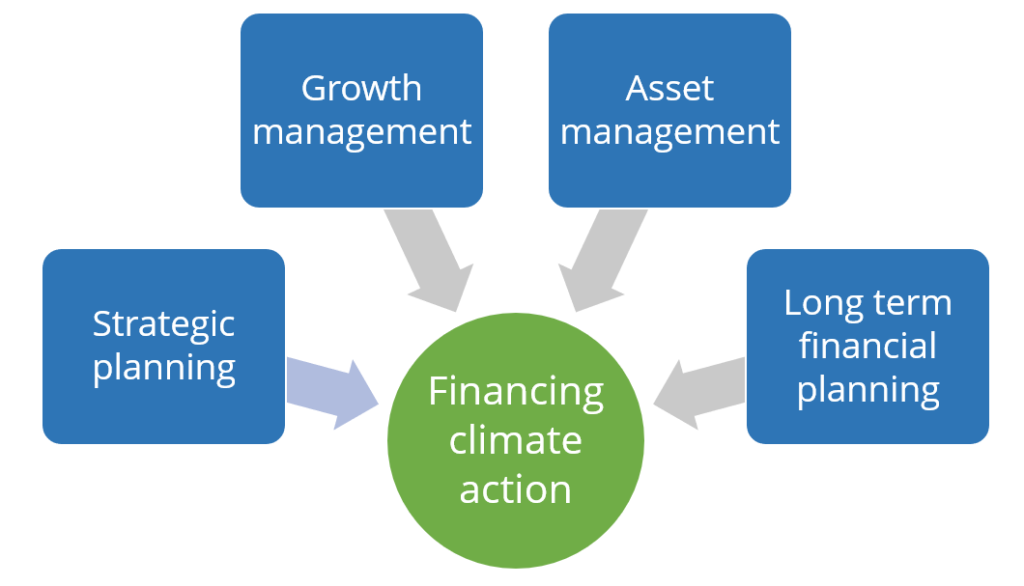

Local governments cannot rely solely on senior government grants and other sources of external funding to address climate change. An integrated financial planning approach considers and identifies risks to long-term fiscal sustainability to avoid unplanned increases in costs or disruptions in services. It prioritizes resources needed to achieve strategic objectives and provide cost-effective service delivery. It also anticipates future known and potential costs to inform significant policy decisions. Consistent, reliable and long-term climate mitigation and adaptation activities will require a thoughtful and integrated approach.

Strategic planning facilitates the setting of council priorities by elected officials. It is also related to budgeting and performance reporting and plays a critical role in providing direction for the three subsequent approaches.

Long-term financial planning helps provide better financial information when municipal councils consider significant policy decisions, including tax/utility rate impact, debt and reserve levels, and value for money.

Asset management helps to identify the full cost or life-cycle cost of assets that are required to deliver sustainable services and thus the capital, operations, maintenance, and replacement costs are critical elements of asset management. Effective asset management has the potential to reduce the long-term costs of infrastructure by reducing borrowing costs.

Growth management helps to minimize the costs of sprawl (including servicing, health, emissions, and loss of greenspace). When integrated with asset management, a growth management lens can reveal cost savings of more compact, complete and connected growth patterns. It also supports the implementation of integrated community sustainability plans and community and corporate greenhouse gas emissions plans and/or climate action plans. Growth management and minimizing sprawl are two purposes of Regional Growth Strategies and Official Community Plans.

LCA is a technique used to estimate environmental impacts, or costs, of a product or project over its entire life. LCA estimates the impacts or costs of resources associated with a project, or a product, from ‘cradle to grave’ – including extraction and processing, use, and costs associated with the product’s disposal. LCA evaluates environmental impacts at all stages of a project facilitating the selection of an option with the smallest environmental impact which is the most cost effective over time.

The key steps in LCA are:

- Defining the purpose of the analysis, identifying assumptions and boundaries, and defining scope

- Compiling an inventory of relevant energy and material inputs and environmental releases

- Evaluating the potential impacts associated with identified inputs and releases

- Interpreting the results to help make informed decisions

LCA can be narrowed to compare options for specific environmental priorities, such as reducing emissions. Carbon footprint analysis, also referred to as a GHG emissions assessment, is a subset of LCA.

LCA is complementary to, but not the same as, life cycle costing (LCC) which looks at the economic costs of a capital investment over its useful life, including operations, maintenance, and replacement.

LCC looks beyond initial capital costs and assesses the costs of assets and infrastructure over their entire life. It is not uncommon for local governments to focus on initial capital cost when investing in infrastructure and other assets, such as fleet vehicles. LCC looks at operational, maintenance, and replacement costs over the life of an asset. This approach can strengthen an organization’s fiscal performance and contribute to reductions in emissions.

LCC looks beyond initial capital costs and assesses the costs of assets and infrastructure over their entire life. It is not uncommon for local governments to focus on initial capital cost when investing in infrastructure and other assets, such as fleet vehicles. LCC looks at operational, maintenance, and replacement costs over the life of an asset. This approach can strengthen an organization’s fiscal performance and contribute to reductions in emissions.

LCC has many applications:

- Procurement of new fleet vehicles, office equipment, and machinery. For more information download E3 Fleet’s Lifecycle Cost Analysis Tool or read BC Hydro’s rational for life-cycle costing.

- In development of transportation and energy systems infrastructure. Asset Management BC provides a framework to support a life-cycle approach to sustainable service delivery.

- In establishing premium efficiency targets for new and existing stocks of civic buildings.

- In supporting the development of residential and commercial buildings.

- In land use planning, notably as it pertains to infrastructure costs. The CLIC Tool compares the life-cycle costs of different development scenarios, while Kelowna used their Model City Infrastructure tool to demonstrate the lifecycle cost savings of complete, compact built form.

In addition to fiscal considerations, LCC analysis supports local government climate change actions. For example:

- Investing in green building features have resulted in reduced energy use. See Qualicum Beach Fire Hall Replacement Project.

- Replacing high emission fleet vehicles with new models has resulted in reduced fuel use. See Saanich’s Fuel Efficient Municipal Fleet.

- Identifying that compact development scenarios are more fiscally sustainable can result in decisions supporting develop that reduces vehicle miles travels. See CLIC Tool case studies.

Life-cycle costing is related to life-cycle analysis (LCA) which is used to estimate the environmental impacts of a project, or product, over its entire life. The phrase “from cradle to grave” is often associated with life-cycle analysis. Using LCA can lead to reduced emissions.

Example: Model City Infrastructure

Model City Infrastructure (MCI) is a new analysis tool developed to assist Kelowna staff, Council and the public as they consider the long-term infrastructure implications of land use decisions. MCI enables the evaluation of the long-term financial performance of various types of neighbourhoods by comparing how much the City spends on long-term infrastructure in different neighbourhoods with the tax revenue and utility fees collected from them.

The MCI analysis focused on lifecycle costs, as opposed to up front capital costs, often associated with assuming infrastructure after development. It demonstrated that more complete and compact areas of Kelowna performed better financially than the areas that are characterized by auto-depend built form and low density and dispersed land uses.

Learn more: