Working together

Collaborative action to support low carbon resilience

A single solution for addressing the impacts of climate change, or mitigating future impacts, does not exist. In other words, solutions that work best will likely be based on collaboration and integration across subject matter areas and professional disciplines. Furthermore, local governments are recognizing that community response to climate change is a shared responsibility that requires the active participation and collaboration of the interested public, governments at all levels, First Nations, business and industry, non-profit organizations, academic institutions, and other stakeholders.

We live in an integrated system where decisions can have economic, social and environmental impacts. Actions taken to mitigate climate change, and adapt to a changing climate, are strengthened by taking an integrated approach. This works best when we collaborate. This includes the participation of those who impact the system, from producers and consumers of goods and services to the creators of policies and programs.

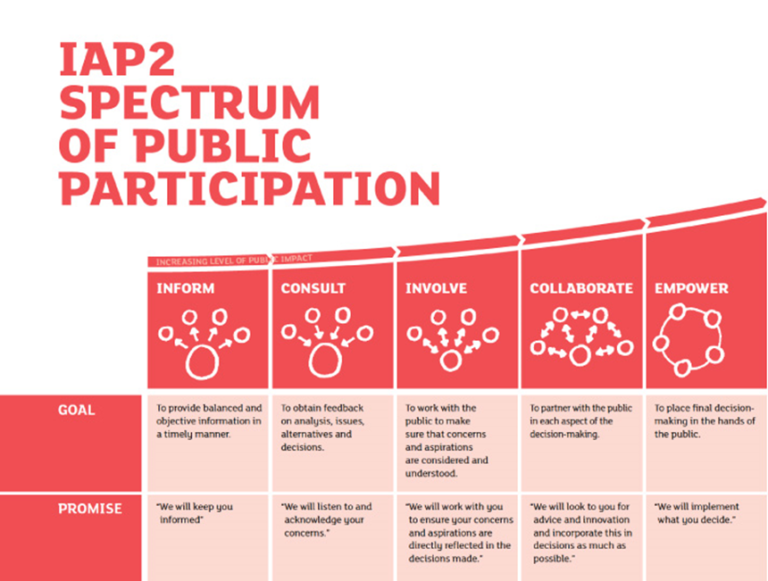

Engagement of the public, local government employees and other stakeholders and collaboration among local, provincial, and federal governments, First Nations, the private sector, industry, advocacy groups, and interested members of the public are critical to the development and implementation of actions to reduce emissions and address the impacts of climate change. Engagement lies on a spectrum: at one end is increasing awareness and seeking feedback, and at the other, fully empowering impacted groups and individuals to identify possible solutions and take ownership in implementing them.

Collaboration

Collaboration is the process of working with stakeholders, interested parties and technical experts from a diverse range of subject matter areas to develop policy and programs and drive implementation.

Collaboration across government, subject matter experts, First Nations, business, industry, and the community-at-large helps to identify challenges, opportunities and interconnections supporting the development of policies and programs that are robust, realistic and implementable. Since emissions mitigation and adaptation efforts require inputs from a range of technical areas and perspectives, working across silos is a natural extension of an integrated response to climate change. It also helps to bring together resources and perspectives to support effective and efficient implementation.

Local governments are supported by a staff with a vast range of perspectives and professional backgrounds. These include engineering, planning, finance, legal, policy, management, public health, social services, recreation, operations, construction, front counter, among others.

Addressing climate challenges, such as building retrofits to increase corporate energy efficiency, or developing stormwater guidelines for municipal infrastructure and private development, generally requires thinking outside a disciplinary silo. For example, local government energy managers or sustainability coordinators may interact with development engineers, transit planners, land use planners, accountants, and solid waste operations staff, all in one day.

This approach is often referred to as working in a way that is multidisciplinary or interdisciplinary. A multidisciplinary approach is when representatives from different disciplines work together to solve a problem, each drawing on their unique disciplinary knowledge. An interdisciplinary approach means that representatives from different disciplines working together, but are synthesizing their respective theories, practices, and approaches.

Given the importance of interdisciplinary responses to climate challenges, the Canadian Institute of Planners (CIP), Canadian Society of Landscape Architects (CSLA), Royal Architectural Institute of Canada (RAIC), Canadian Water & Wastewater Association (CWWA) and ICLEI Canada published a joint statement in 2018 on advancing climate action. It commits the associations to, among other things, advance shared understanding and ownership among members for integrated climate action and advance interdisciplinary capacity for integrated climate action through collaboration between associations and enabling collaboration among members.

One method to support cross-silo collaboration is a low carbon resilience community of practice. A community of practice (CoP) is a group of people who share a common concern, a set of problems, or an interest in a topic and who come together to fulfill both individual and group goals.[1] Such a CoP could support learning and development, identifying opportunities for climate action, and sharing resources between departments and disciplines.

Learn more about creating communities of practice (Edmonton Regional Learning Consortium).

Local governments have unique resource to help them in their climate action efforts: each other. Other local governments of both similar and different contexts are a great place to learn about implementation of climate solutions, including helping to identify approaches that work best, data insights, and practical advice. Peer-to-peer networks and learning hubs provide a place for local government staff and elected officials to share information and identify opportunities to collaborate. Examples include:

- Partners for Climate Protection Hub (FCM) is a peer-to-peer online network that helps municipal staff and elected officials connect with the best resources and expertise on local climate action. The hub is a great way to learn about the latest resources on climate and energy and to get news about funding opportunities.

- Energy Step Code Peer Network (Community Energy Association)

- CEEP QuickStart Community of Practice (Community Energy Association)

Engaging internally

Engaging local government staff and demonstrating leadership on climate action is essential to meeting the goals of the Climate Action Charter. Implementing an employee engagement strategy builds local government credibility in terms of public perception of climate action. The process of engagement can shift thinking and fosters the creation of new social norms. Creating this buy-in from staff will build support for the investment of initial financial costs associated with upgrades, retrofits, and climate action programs.

Buy-in starts with senior management, who can build understanding around climate change issues by defining climate action and making emissions reduction activities a corporate priority written into policies, decision–making procedures and reporting.

- Make climate action a corporate priority. Interdepartmental managers can build synergies across departments and provide opportunities to coordinate greenhouse gas (GHG) reduction initiatives related to the Charter.

- Other awareness-building activities such as informal lunch-and-learn sessions with staff engaged in climate action projects and presentations at departmental staff meetings. Consider bringing in experts such as local energy associations or other non-profits to speak at sessions with elected officials and staff. Try out fun and engaging problem solving and learning techniques such as design thinking and world cafés.

- Partnerships, learning opportunities, and the sharing of resources, across local governments and with First Nations communities can build long-term regional resilience.

- Create actionable items for employees and departments. These projects could be based around a green procurement or ethical purchasing policy, cycle commuting programs, developing green design guidelines and operations procedures, and infrastructure solutions

Learn more:

- Local government and First Nations engagement methods such as the Community to Community Forum

- “Cross-Silo Leadership” (Harvard Business Review)

- Dialogue and Facilitation Tools (SFU Morris J. Wosk Centre for Dialogue)

- Design Thinking Resources (Stanford d.school)

- The World Café: techniques for engaging people in conversations that matter

- Open Space, a framework for running productive meetings and events

Engaging externally

At its most basic level, public engagement is providing the opportunity for interested parties affected by a decision to have input into that decision. In this regard, engagement activities are typically designed to meet statutory requirements. However, public engagement can go beyond basic requirements and provide tremendous value in activating public support, identifying and responding to potential issues early, and finding solutions in a collaborative environment that reflect the interests of multiple parties.

Engaging community-members and other stakeholders is a key step in advancing a community’s climate action strategy. This might include educating the public on the full costs of services of local government operations and the implication of climate actions.

Effective engagement supports leaders and decision-makers, so they better understand the perspectives, opinions, and concerns of citizens and other stakeholders. This can help in developing public support for policy and actions related to climate change mitigation and adaptation.

Effective engagement results in a clear understanding of the challenges and opportunities that arise from climate action. Comprehensive engagement strategies can facilitate individual and group participation in implementing climate actions.

Engagement frameworks, such as the one advanced by the International Association for Public Participation (iap2), are available to help local governments plan, structure, and execute their engagement efforts. In iap2, there are five levels of public engagement, ranging in outcomes and intensity of effort.

This spectrum of engagement levels does not imply that “higher is better.” Rather, they allow local governments to select the appropriate level of engagement based on the issue at hand. For example, a replacement of a section of stormwater pipe may be under the inform level. Alternatively, consultation during the preparation of a stormwater and utility climate and adaptation plan may be under the consult or collaborate levels.

Most engagement approaches will combine awareness building, collaboration and action. The first step is ensuring you have a clear understanding of:

- Why engagement is necessary? What is the purpose? What are the outcomes for the initiator of the engagement process? What are the outcomes for the participants of the engagement process?

- Who do you want to engage? There are many “publics” that exist. Get specific about the population that you want to learn more about. Is it a particular business sector, neighbourhood, demographic?

- What do you want to engage them on? There are different methods for engagement depending on the intention. Is there a decision to be made, a question to be answered, a problem to address, an opportunity to look at, or a relationship to build?

- How will you engage the public? There are many engagement methods out there. Rather than getting overwhelmed with methods, they key is to be clear about the intention, goals, outcomes, and principles. Then, you can find the methods that suite your purpose.

Benefits of using a well-defined engagement framework include:

- The scope and outcomes of the engagement are defined, and it is clear from the outset what the local government and interested parties can expect to achieve from the process

- Expectations are managed such that the intended process or steps to be undertaken by the local government are shared with interested parties in advance

- Conflict is reduced or avoided because the local government and interested parties have opportunities to be heard, to identify potential issues early and to develop mitigation or alternative solutions

Tips on communications and public engagement in general:

- Explain the community–wide targets and invite community-driven descriptions of what reaching the successful target will look like. These might include cleaner air, less traffic outside schools, lower energy bills, enhanced local tourism, etc.

- Look for opportunities for strategic partnerships that could help build capacity towards meeting community-wide climate goals. These might include the school district, local business association, or local environmental organization. Build on existing relationships and take advantage of any special skill sets existing in the community.

- Plan to reach your community outside of the local government office at venues where community groups gather. Consider a wide range of outreach methods such as travelling roadshow at schools and community events, information booths and festivals and events, webinars, community meetings, presentations, speakers, film nights, distributing a mayor’s message, rural advisory groups, public meetings, design charrettes, open houses, task force, web polls, software to vision land use, and citizen steering committees.

- Keep the message positive, upbeat, and focussed on solutions.

Further guidance and frameworks for public engagement:

Community-based Social Marketing (CBSM)

CBSM is one way to inspire the public to take climate action. Many of the actions that support emission reductions, like shifting to active transportation or reducing energy use, and to support climate change mitigation, such as using less water, require people to shift behaviours in their daily lives. Therefore, CBSM combines commercial marketing tools with those that have been identified as being particularly effective in fostering behavioural change.

Key community-based social marketing tools include:

- Prompts: reminding people to engage in sustainable activities – such as sticker on a vehicle indicating that the driver does not idle

- Commitments: have people commit or pledge to engage in sustainable activities – for example signing a pledge card to avoid unnecessary vehicle idling

- Norms: develop community norms that a particular behaviour is the right thing to do

- Vivid communications tools with engaging messaging and images.

Community-based social marketing is also pragmatic. As such, it involves:

- Identifying the barriers to a behaviour

- Developing and piloting a program to overcome these barriers

- Implementing the program across a community

- Evaluating the effectiveness of the program[3]

Learn more: