Sustainable site design through development permits

A Development Permit Area (DPA) is a set of development regulations pertaining to a specific area as specified by the Official Community Plan. Any proposed building or subdivision within a DPA requires the issuance of a development permit. The authority for local governments to establish DPAs is set out in the Local Government Act.

The purposes of a DPA are:

- protect development from hazardous conditions;

- protect agricultural land;

- protect the natural environment, its ecosystems and biological diversity;

- revitalize an area in which a commercial use is permitted;

- establish objectives for the form and character of intensive residential development, and/or to establish objectives for the form and character of commercial, industrial or multi-family residential development.

- establish objectives to promote energy conservation, water conservation, and reduce greenhouse gases

The flexibility of DPA guidelines allow local governments to exercise their discretion in granting or refusing a permit on a case-by-case basis while providing objective principles to guide conditions for approving or refusing a DP application. [1]

Complementary Measures

- DPAs can be developed through an Official Community Plan and Neighbourhood Plan.

- DPAs work in coordination with a Zoning Bylaw to shape development on the scale of a parcel or development site. Comprehensive Development Zones can be quite specific, working well in tandem with DPAs.

- Development Permit Areas can stipulate conditions for Density Bonusing.

- Standards and designs for streets (e.g., “Complete Streets”) specified in Subdivision and Development Control Bylaw must be consistent with DPAs objectives.

- The key objectives of the DPAs can be represented in a Sustainability Checklist.

A versatile policy tool

A DPA is a versatile design tool that can be designed to influence emissions from land use, buildings, and transportation. There are some key implementation considerations in applying DPAs to address climate change priorities.

Key Implementation Considerations

In setting guidelines for a DPA, a local government may not require buildings to meet standards that exceed a local government’s authority over building standards. However, local governments may encourage green building standards by indicating they are desirable.

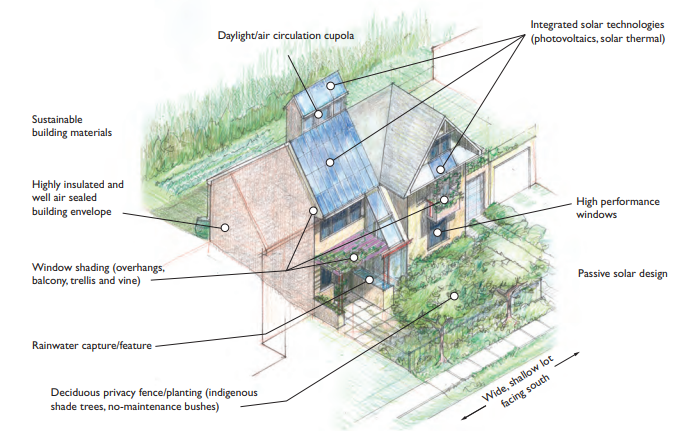

The scope of authority for DPAs does not include buildings (inside the building envelope). However, it allows for DPAs that promote energy and water conservation and reduce greenhouse gases at the site scale. This includes:

- landscaping

- siting of buildings

- form and exterior of buildings

- specific features in the development

- machinery, equipment and systems that are external to buildings.

Measuring performance

The Local Government Act requires local governments to develop targets for emission reductions and report on progress. Local governments can tailor DPA guidelines so that development will contribute to specific measurable targets for the community.

Process of Creating DPAs

DPAs can be created during an Official Community Plan and/or a Neighbourhood Plan process. To have a robust planning framework, there must be continuity and support between the policies, land use designations, and DPAs.

Land Use Opportunities

Complete, compact neighbourhoods

DPA guidelines define the form and character of new developments, with the following applications:

- areas of intensive residential development (ex: small lot areas, infill areas)

- mixed use development

- multiple family residential development

- commercial areas

DPA guidelines develop continuity and set parameters for performance of new developments. DPA guidelines are not intended to foster monotony or uniformity in design.

Good planning and design-including DPA guidelines-are the foundation for creating compact communities where people want to live. Success requires deliberate planning for the mix and density of land use, and design is of utmost importance: “How we perceive density has everything to do with how it is designed, not the actual ratio of units to acres,” according to the Lincoln Institute [2].

DPAs are essential in guiding new development that will be supported by residents and fit in with the character of existing neighbourhoods.

Ecologically significant areas, natural hazards, and agricultural land

To maximize the benefits of compact and complete communities that concentrate growth, DPAs can be used to protect ecologically significant areas, natural hazards, and agricultural land – objectives that increase resilience to climate change and enhance carbon sequestered in soils and forests.

Building Opportunities

In setting guidelines for a DPA, a local government cannot require buildings to meet standards that exceed a local government’s authority. However, local governments may encourage green building standards by indicating they are desirable. For example, the DPA guidelines for the Dockside Green project in Victoria indicate that LEED standards are a “should” whereas other DPA guidelines are stipulated as mandatory elements. A separate master development agreement was negotiated by the City and the Dockside developer for LEED Silver standard. [1]

Form and character

Building design guidelines that advance climate action include:

- glazing and orientation for solar energy gain

- landscaping that requires less water

- drainage by infiltration, maximizing pervious surfaces on the site

- natural ventilation (to reduce cooling loads) [4]

More information, see EQuilibrium: Healthy Housing for a Healthy Environment.

Energy efficiency, water efficiency and reduction in emissions

One approach is to develop voluntary design guidelines and encourage uptake with incentives like a tax exemption or building permit rebate. Subsequently they could be formally included in a DPA.

Guidelines could potentially include requirements for energy efficiency for “specific features in the development”, or as “machinery, equipment and systems external to buildings and other structures”. Requirements could include ground-field loops for ground-source heat pump systems, solar thermal collectors, a district energy system (using recovered sewer heat or biomass), and systems or features that implement eco-industrial networking concepts, such as the use of “waste” heat from one business as an input to a neighbouring business. [3][4]

To meet legislated requirements for targets and reductions, local governments could potentially develop an energy conservation target for a DPA and correlate the target with a required proportional component of renewable energy in new development. [3][4]

With the authority to include specific landscaping guidelines, DPAs can restrict the placement and type of trees and other vegetation in proximity to buildings and other structures within a DPA, thus allowing local governments to guarantee access to sunlight for buildings that include solar energy features [4], and irrigation systems. Additional opportunities include guidelines for energy-wise outdoor lighting, building siting and orientation. [3]

Transportation Opportunities

Form and character guidelines for site and building design can include elements that favour sustainable and active modes of transportation.

Site layout

Internal transportation network configuration determines how pedestrians, cyclists, carpoolers, transit riders move through the site. Guidelines can influence design to minimize conflict between pedestrians and cyclists with cars.

Building design

The location of the building (setback, location of entrances, organization of parking) affects how conducive the building is to active transportation modes. Well-designed bicycle storage, parking space allocation, pedestrian walkway details, change facilities, and lighting can tip the balance toward choosing an active mode of transportation.

DPAs are an excellent opportunity to require site and building design that allows people with varying mobility and sensory abilities to efficiently get to, from and around new developments. DPAs can include requirements for entrances, hallways, entryways, parking areas that facilitate unrestricted movement.

More information:

See Development Permit Areas for Climate Action for guidance on climate supportive DPAs, examples and case studies.

Examples:

- Esquimalt (Energy conservation and greenhouse gas reduction, hazardous conditions, water conservation, natural environment)

- Fort St. John – Parkwood Southlands / Fish Creek (Energy conservation and greenhouse gas reduction, natural environment, hazardous conditions)

- New Westminster – Mainland Industrial (Energy conservation and greenhouse gas reduction, natural environment)

[1] Rutherford, Susan, 2006. Green Buildings Guide. West Coast Environmental Law

[2] Campoli and MacLean, 2007. Visualizing Density, 2007, Lincoln Institute of Land Policy

[3] Compass Resource Management Ltd., West Coast Environmental Law, Holland Barrs Planning Group, Shaun Martin Consulting Prepared for: The District of Squamish, 2008. Advanced Briefing of Options for Advancing Energy Efficiency for New Buildings.

[4] Community Energy Association, 2008. Policy and Governance Tools: Renewable Energy Guide For Local Governments in British Columbia (Draft).